07 Dec “Danas” newspaper journalist on the FOLIO festival and CELA project – Serbs at the literary festival in Portugal: How to translate ‘dom zdravlja’ into foreign languages, and other legacies of times long gone

Source (in Serbian): danas.rs – first part, second part

Text and photo: Nina Čolić

“The reading of all good books is like a conversation with the finest minds of the past centuries” said Descartes, probably not even suspecting that one day, centuries later, he would be considered one of the greatest minds in human history.

The emergence of the Internet enabled rapid connections between people all around the world, so we could say that Descartes’s thought started gaining new forms and meanings. Where people are, there is art, and therefore also literature.

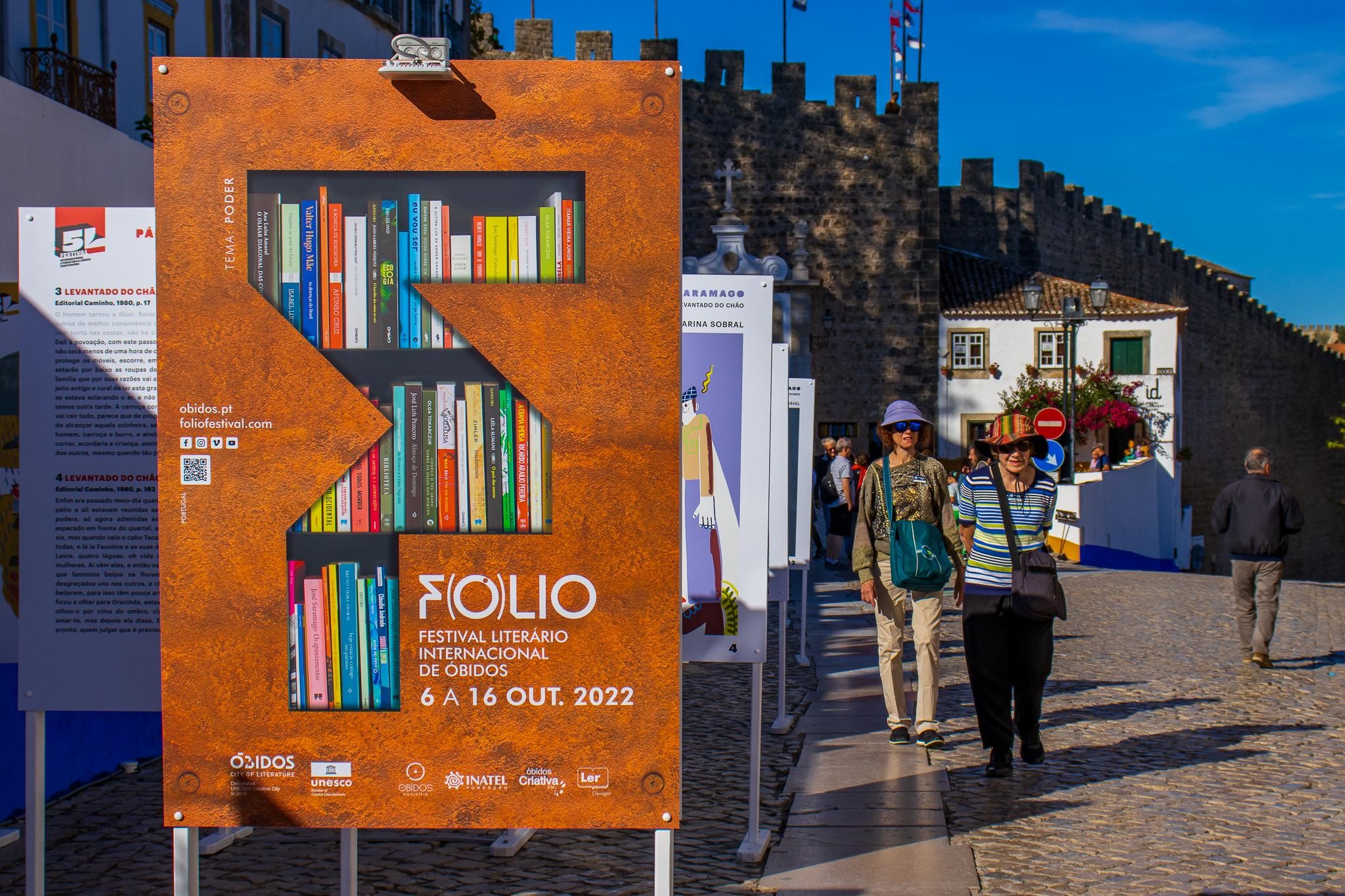

Making such literary connections happened last month in Portugal. Under the CELA Project, in the implementation of which the Association KROKODIL takes part, and which will be described below, the writer Jasna Dimitrijević and translator Ilija Stevanovski took part in the FOLIO literary festival.

“Only when the first draft of the translation has been done can I think about Ana’s prose as a work of art. To me, every text is a riddle that I’m trying to solve at so many levels, a figure of lego cubes which I first need to disassemble, study the notches and connections of each element, then assemble it again as much like the original as possible, working with a slightly different set of parts. I was lucky to receive some of Ana’s instructions, noted in the comments of the document, together with the manuscript. By ‘dom zdravlja’ it said: ‘do not translate as health centre, out-patients, etc. ‘Dom zdravlja’ as in ‘Dom omladine’, ‘Dom sindikata’, ‘Vatrogasni dom’. For work stoppage she noted: ‘not strike’. Regarding basic units of joint labour, the comment was: ‘I think this is understandable, let me know if you need a clarification’. ‘There were many ‘doms’ in this socialism of yours’, I note in the file. I put a smiley, I don’t expect an answer.” This is an extract from a text by Jasna Dimitrijević which was translated live into Portuguese in this project.

However, before we turn to the Serbian representatives and their participation, we must take a look at the host and its importance – the City of Obidos.

A small town with a little over 3,000 inhabitants but more than 10 bookshops.

Once a wedding gift for queens, the well-kept medieval town of Obidos, 80 kilometres north of Lisbon, is undoubtedly one of the most interesting Portuguese towns.

Traces of different civilizations are seen at almost every step of narrow cobbled streets.

From hidden angles and high walls that make a special kind of labyrinth, the town is a huge work of art which was carved, destroyed and renewed throughout the centuries.

The Project Obidos Vila Literaria started in 2011 with the goal of opening a path to the reconstruction of the historic centre of Obidos.

This popular tourist destination has already become famous for several events, such as a Medieval Market, a Chocolate Festival, a Christmas Village and an Opera Festival.

However, Obidos had to find a new strategy, and chose literature as a way to a new future.

The whole Project started because of the need for renovation works on some buildings and public areas for which finances were sought, especially for the restoration of the old church located within the walls.

In a country that just over a decade ago was unable to finance maintenance and heritage programmes, solutions had to be found that aimed at the cultural and economic dimensions of the area while respecting architectural history. The strategy was to create a cultural and literary centre in Obidos.

“When we opened the largest Portuguese bookshop in a church in 2012, we turned everybody’s attention to new configurations between the space and activities and between domestic and foreign talents. Our starting point was to build a physical network of bookshops, which grew into 11 new ones in less than five years, including a literary hotel. This project positioned Obidos in a very interesting way, not only because of its cultural importance, but also because of tourist differentiation”, explained a municipal official.

On December 11, 2015 UNESCO declared Obidos a literary city, in the Creative Cities Network Programme.

Created in 2004, this network aims at “promoting cooperation between the towns that have identified creativity as a strategic factor for urban development”.

Obidos’ application for the UNESCO Creative Cities Network is, among other factors, based on the project Literary Village which has been developed in Obidos since 2011.

Obidos Vila Literária is a unique project in the context of art and cultural events that take place in Portugal. The quality of this literary and artistic project is recognized by the local, regional, national and international community, as well as by the public both locally and globally.

The Literary Village Obidos was created on the assumption that there will be a network of bookshops equipped with special facilities for organizing art exhibitions, concerts, conferences and performances.

“Apart from spaces with books, Vila Literária includes a range of municipal facilities: museums, galleries, art and literary residences, which enabled us to complement our offer and meet writers’, authors’ and artists’ demands as they seek Obidos as the place where they can develop their projects or present them”, says the explanation.

Activities in Vila Literária last throughout the year, with the more important events at festivals and literary and artistic gatherings – at FOLIO, an International Literary Festival (with its various and artistically understandable components), and in Latitudes, which connects literature and travel.

At this moment and in general, Obidos is a literary city because it includes literature in everything it does – from the reconstruction and reuse of old buildings to the creation of jobs and ideas about alternative tourist products.

How did it look like on the spot?

This town with a little over 3,000 inhabitants within its walls can boast of more than a half a million books.

So as not to finish this only with the words of the Obidos officials, several lines about the “on the spot” experiences can’t do any harm.

The first thing that you can’t miss upon turning off the main road is the outline of the fortress and walls that speak clearly of the centuries of existence of Obidos. However, as this is a text about the literary face of the said city, we can immediately jump over the former, and move on to the latter.

It is all about books, at least at the time of the festival. Bookshops are almost everywhere, considering that the old town, which is the main attraction, can be visited in a couple of hours. But it’s not easy to find them.

Books alongside food and spices? Obidos has managed to connect them. Shops with souvenirs of wrought iron and sets with a fountain-pen? Obidos made this happen, too. The town library named after the famous Portuguese writer Saramago? This too you can see here.

Talking to local people I had the opportunity to learn about “the hidden” gem of love for the written word. Nearby the place where I stayed there is “The Literary Man Obidos Hotel”.

Inside it hides an empire of books – over 65,000 books decorate rooms and hallways. This is heaven for admirers of the written word. According to some this is the largest “literary hotel” in the world.

People organizing the FOLIO festival point out that the hotel works only during the festival period – ten days a year. But a little search on Google shows that there must have been a little “mismatch” between what they were trying to explain to me and what I understood. It seems as if something was lost in translation.

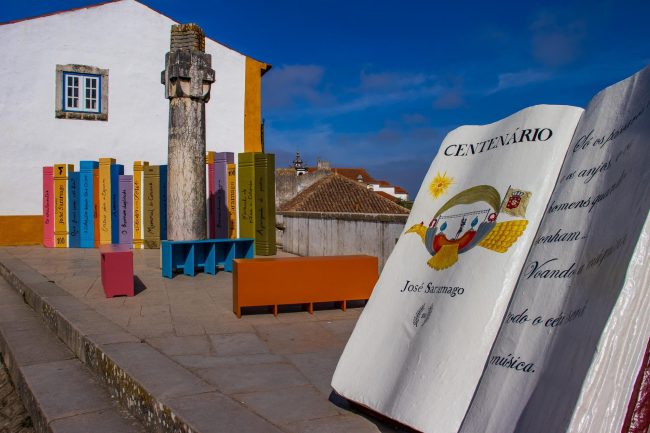

One of the squares was decorated with statues that are supposed to symbolize books on shelves, as well as an open book with Saramago’s name and a quote.

“The only ones to fly are birds, angels and people in their dreams. Flying in a machine turns the whole sky to music.” This is the closest to a Serbian translation of Saramago’s quote that can be obtained via the Internet, since a translation into English is nowhere to be found.

In the main street you can also see a golden bike with a basket full of books, though like in other places, they are all in Portuguese. Even the side streets, just like in an Easter egg hunt, hide thoughts written on the facades, but not like graffiti, they are actually placed according to a plan.

The church of St. Jacob is one of the most unusual monuments of Obidos.

On their way to Santiago de Compostela, pilgrims would usually stop at this church, before it was completely destroyed in an earthquake in 1755. It was renewed in 1772, but little of the original church decoration remained.

Books, mostly in Portuguese, but also in English and other languages, are now placed around the altar and fill the inner space, making this place literally a temple of books and literature in general.

The town’s library doesn’t lag behind, not a bit. It is placed in the very heart of Obidos, with a view of the square where the festival takes place. This is another small empire of books extending over three floors.

In the library itself, besides the corner devoted to the man whose name the library bears, “Casa José Saramago”, a special place is reserved for a big collection of records and journals, but also a room where literary evenings and lectures take place.

It is of course possible to buy a book as a gift, but there are also many other items that have literary motifs or are used for creating great future writers.

One festival day: The first part or when you don’t understand your host’s language

On the festival day for which I was in Obidos, on behalf of the Association KROKODIL and the CELA Project, there were two events.

Besides the panel with the participants from Serbia and Romania, which I was most interested in, there was a debate between two Portuguese authoresses Daniela Costa and Patricia Patriarca.

Since it was all in Portuguese, I could not understand their talk and the parts of text they read live.

However, while Daniela Costa read, the power of emotion that lies within literature and creation was shown in the best possible way.

Barefoot, only a couple of metres away, it seemed as if at that moment and in front of the people, she was pouring out all the emotions she was going through again and again while reading the words written a long time ago.

It sounded beautiful. Perhaps the literal meaning escaped me, but the essence was easy to understand through the emotion.

The talk was over, there was a break for a cup of Ginjinha, a national Portuguese drink, followed by the main reason for my visit to Obidos.

One festival day: Second part or how to explain concepts typical of Yugoslavia

At a panel moderated by Portuguese journalist Vanesa Rodriguez, two authors, Jasna Dimitrijević from Serbia and Lavinia Braniste from Romania, were presented to the audience in Obidos.

However, as the very goal of the project is to spread literature beyond the context of its original language, the role of a Serbian-to-Portuguese interpreter was taken by Ilija Stevanovski and that of a Romanian-to-Portuguese interpreter by Cristina Visan.

First, the panel moderator gave the floor to the Romanian duo who opened the second panel of the CELA project by taking turns reading in Romanian, then interpreting into Portuguese, parts of a text by Lavinia Braniste.

“As an old man Grigore stayed away from people. There was a multitude of movements he performed in secrecy. These were small and inconsiderable things and precisely that’s the reason why it seemed to him they were easy to hide, but they accumulated. He didn’t want to be criticized for being weak. In his youth he was brave, but his bravery was limited. It soon wore off.” This is a part of the text of Lavinia Braniste which was created within the CELA project on the subject of Change.

“I think it’s brilliant that ‘small’ languages and cultures have the opportunity to discover one another”, said Braniste, talking about the project.

Commenting on the writing process, Braniste pointed out that the limitations within the project such as the 10,000 characters she had to bear in mind, posed a challenge.

“This is about five pages, which is extremely short for a writer of long stories like me. Only when I started writing, I realized it was actually an introduction to something bigger. I plan to write a novel and this is just the beginning”, she said.

As she pointed out, writing and translating are very individualistic jobs, in a way characterised as “solitary”.

“I think that both writing and translating are ‘solitary’ jobs. I translate literary texts myself, so I can identify with translators. I think these events are important when a translation has been made, so that some questions could perhaps be answered, or authors could be contacted and doubts clarified. Surely, both processes are very ‘solitary’, said Braniste.

Braniste also announced this was not the end and that the text would become a novel.

“I can speak from my own writing, or rather as I used to write. I think this has marked a change in the way I write, as it is different from my previous stories that featured narration in the first person singular, as well as the focus on female characters and their stories. This novel will be a story about a relationship between a father and a son, which is a challenge for me. Also, there will be changes in the characters’ lives, this is just a beginning. Through this introduction you have been introduced to the characters who will experience changes due to various events”, said Braniste.

Then Dimitrijević and Stevanovski presented themselves to the audience.

“It may seem to you that the country exists only in those collections of non-existent terms”, says Ana, “but I won’t take your remark amiss. Other people’s lives, other people’s past, other people’s reality. What makes me sad is the fact that a dismal number of its inhabitants behave as if this was about a change of natural phenomena when they talk about the change of a social system. It was raining, now it’s snowing, tomorrow it will be windy. Or, even worse, as if Yugoslavia disappeared like a fucking Atlantis – sank in the sea, and maybe it didn’t even exist, only a myth, a story impossible to verify so anybody can add to it as they like. Or to negate it completely. Then Ana talked about health care, women’s right to vote in 1945, workers’ flats and vacation spots, free of charge education. But I was still thinking of the ‘Atalantis’, part of Jasna Dimitrijević’s text, which will, entirely and as expected, later on occupy the majority of the talk about her writing.

After the reading of the text by the Serbian participant, a talk and debate ensued.

“Your text is extremely political and ideological, but is also meta-translation, considering the fact that it precisely deals with translation, which is very interesting. We have the original text, translation and then discussion which has to do with the translation of the text”, remarked the panel moderator.

As Dimitrijević explained, she tried to cover the assigned topic on several levels.

“Actually, when we received the invitation to write on the topic of “Change”, it was the first time I knew I would write a story which would have to be translated. Usually when I write, I don’t write thinking that people will read it in another language. I tried to ‘walk in the translator’s shoes’, and that life isn’t so easy. I was thinking of the changes of terms, transformations actually at three levels. First, the big picture – historical changes, political and ideological, then personal changes, as well. Which events make an individual change? At the third level there was the change of language. Why do we learn to translate? What do we do with the language? Sometimes we need to make many changes for things to stay the same, to make them precise, which, I would say, happened in this translation that Ilija made. How do we choose which changes to make so that something would be better? Briefly, this was what I thought about while writing the text”, clarified Dimitrijević.

As the panel moderator described, the text represented a reflection on past times that span up to the present and try to explain the political and ideological context that the author lives in. The changes Dimitrijević wrote about didn’t happen only on paper.

“The text no longer belongs to me. As I said, while I was writing I thought that the first readers would read it in eight different languages. The plan had never been to publish it as a part of a larger literary work, but only in a magazine. For me this was an experiment in that concrete context – for the CELA project, to tell a story to translators and communicate with them, to give them a difficult task, but also provoke a dialogue among all of us”, she pointed out.

The names of institutions that have been used since the time of Tito’s regime presented the greatest challenge.

“I don’t even know how to translate certain terms that once existed in communist Yugoslavia. They actually still exist now and are used today. For example, ‘dom zdravlja’, even though we live in capitalism. The term stayed, but the meaning changed. The text no longer belongs to me, I stopped having any influence on it. The only thing I think about from time to time are some statements by characters from the text, and that happens when I get feedback from somebody who read it”, said Dimitrijević.

When asked whether in Serbia people still talk about topics related to past times which must have influenced the present, Dimitirijević pointed out that this could be answered both positively and negatively.

“In my social ‘bubble’ we discuss these things. But I’m not sure if this is a topic in general. Anyway, I don’t really go out of my ‘bubble’, so I can’t say. Actually, it is a topic. What was good in socialism, what was bad and how we can use that experience to make things better than they are in this bad capitalism. How can we learn from that experience and whether we learned something? That is something I love to discuss, both with people, and through literary creation”, emphasized Dimitrijević.

One of the important factors for a good translation is surely good cooperation and communication between author and translator.

“I think we communicated well. Sometimes we ‘slept on’ some solutions and returned to them afterwards. What I consider extremely important for such cooperation is transparency. When neither I nor he can explain something, that’s OK, as in every relationship. That represents an important part in joint work. Text is important to me, but during the process it becomes his text that is also important to him. When he needs to sign it using his first and last name, it becomes ‘our’ text”, she explains.

Dimitrijević stressed that she also experienced a big change thanks to this project.

“The whole project gave me an opportunity. I can approach other people, primarily publishers, even though I still don’t know how. But the first step was taken and I am extremely grateful to the CELA project, KROKODIL in Serbia and all of you, because it gives us even this small opportunity to find readers in other languages. I have not taken part in such projects before. This is a big change for me. I have never imagined that I would sit, listen to and later on discuss things with authors from Romania, Portugal, but also Portuguese journalists. As if one small border has been crossed”, concludes Dimitrijević.

Even though he is very eloquent, Ilija Stevanovski didn’t really speak much at the panel in English. In the debate, he demonstrated his knowledge of Portuguese, so the listeners who don’t know it, weren’t able to understand a number of things.

When asked if he thought that something was “lost” while translating the text of Jasna Dimitrijević, in other words if important parts were weakened by the translation process itself, Stevanovski said he thought they weren’t.

After the panel was finished, without even thinking about which way the day could go, a true connection was made.

Till late at night, the Serbs, Portuguese and Romanians and a few casual passers-by sat at the same table and, colloquially put, “thrashed out” all kinds of current issues. Everyone discussed their own reality and tried to depict it to others, which, by a rough estimate, happened in the end.

The talks lasted till late at night and what happens in Obidos stays in Obidos.

The texts of the authors who appeared at the FOLIO literary festival in Obidos are available at CELA project website.

DISCLAIMER: The text originated within the CELA Project, under the auspices of the Association KROKODIL.

ANTRFILE

What is the CELA project?

The CELA project (Connecting Emerging Literary Artists) gathers young and emerging literary creators from ten European countries to build connections between writers and their translators, to maintain and promote variety in literature, but also to offer greater opportunities to small languages in the field of publishing.

At the moment the project includes 30 authors, 79 translators and six literary professionals. CELA took its first steps in 2017 and in its second edition the project was considerably expanded, and now it includes eleven organizations from ten countries: Belgium, the Czech Republic, Italy, the Netherlands, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Serbia, Slovenia and Spain.

The Association KROKODIL is one of the partners in this project, and with the participation of six CELA participants at this year’s KROKODIL Festival, the European festival tour has officially begun during which all of the authors and their translators will have the opportunity to present their work at literary festivals in partner countries.

Till June 2023 the focus will be on international promotion and career development, which will include the presentation of CELA and its participants at European literary festivals, international marketing and commercial campaigns, a digital “tour” with the texts and translations placed on online platforms, a presentation of the project at Frankfurt Book Fair, representation at national book fairs in CELA countries and/or meetings with local publishing houses.

Activities over four years, which is the planned duration of the current, second phase of the Project, involve a mentoring programme for the participants offered by professionals in the sector, promotion and building of the CELA brand across Europe, and educational programmes for the participants and the audience.

A CELA brochure in which you can find all of the texts in Serbian, except for the works of the authors from Poland, is available on this link.

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.